|

|

| Feedback |

|---|

Real Resources Review: A little makes a lot?I sent John Busby's 7th August article to a friend who understands more about nuclear power than I do. His reaction was that 'Mr Busby is not conversant with the concept of pebble bed reactors'. I would like to ask Mr Busby how he views that technology and whether he would care to tackle it in an article for the uninitiated like myself? Kind regards, Paddy Imhof

The problem is that mining of uranium is running down, whatever form of reactor is envisaged. See Die Welt which reports the imminent closure of some of the French reactors due to fuel shortages. The thorium alternative and fast breeders are dependent on vast development programmes which with the rapid and progressive failure of the nuclear industry will never be funded. As far as the pebble bed reactor is concerned it depends on the integrity of the pebbles and as these contain graphite this is likely to lead to the demise of this technology. The seven UK AGR's are likely to close prematurely as the graphite moderator blocks are disintegrating due to the irradiation which causes structural breakdown. Also there is an overheating due to the Wigner Energy effect which leaves a residual heat in the graphite. The gas-cooled fast reactor is also an unlikely candidate for funding for this reason as it relies on graphite moderation. The nuclear lobby in desperation is arguing that uranium can be extracted from the earth's crust and seawater and looks to fast breeders to generate ever more plutonium. All of which is fantasy. We do not have to wait too long for some of the

lights to go out in France, which will hopefully lead to a reality

check! |

| Singing the nation electric, part 2: post-oil democracy |  |

|

| By Jon Rynn | ||

| Aug/14/2007 | ||

|

Before fossil fuels and industrial machinery transformed the way goods and services were produced, all societies had an energy problem. Some wind power and hydropower was used, but the main energy sources were humans and animals. For the powers-that-were, slavery and serfdom were convenient ways to ensure an adequate supply of human-sourced energy. What will happen when fossil fuels are no longer available; will the global elite be in a position to reimpose serfdom and slavery? The road to serfdomFor the Roman empire, the critical input was the farmland that fed the slaves that built the infrastructure and fed the soldiers that conquered the empire that Rome built.[1] For the French and British empires in the 18th century, it was pretty much the same thing; and the Americas and Russia, and the Turks and Chinese, all kept their empires together by tightly controlling the labor of the workers of the land. But by 1870, all of that was changing. The North had defeated the South in the United States; the Russians had more or less freed the serfs; and the Turkish and Chinese empires were on their long course downward. World War I cleared out much of the pre-existing social hierarchies — that is, king-centered political systems — and World War II was a final attempt by the historically slave-and-serf-owning classes to reassert themselves, dressed up in various forms of fascism. The post-World War II period saw the triumphal spread of a new, nonslave-based society, now fossil-fuel-based, with everyone a king of their own castle. Suburban sprawl gripped the land, made possible by the automobile which was made possible by petroleum. In the U.S., most people were (and are) so busy enjoying or pursuing this American Dream, that they haven’t seemed to notice that a new hierarchy is forming, that we are now on the second generation of the House of Bush, which may be followed by a queen from the House of Clinton.

As long as the fossil fuels hold out, the global elite can continue their reign and expansion without enslaving vast numbers of people. The legitimacy of the system can be maintained, because even a billion people in China and a billion in India can still hope that they can join the post-slave automobile-centered society that the United States pioneered. Meanwhile, the food, manufactured goods, energy, credit, housing, transportation, and security will be controlled by an ever more focused group of institutions.

The road to democracyUnless, somehow, the civilization is restructured to be a more democratic, sustainable type of economic system in which fuels are not needed. There are three components that will lead us away from a new serfdom:

For number one, assuming, in the US, that enough of the republic still exists to allow the citizenry some decision-making power, the most straightforward way to avoid enslavement is simply to make all companies employee-owned and operated. Even without that step, the populace will have to lose some of their antipathy to government intervention in the economy. For number two, if we start the transformation when we still have fossil fuels, it will be easier to create the economic means for a transformation. So, third, we still need a plan for the transformation. With respect to energy, we must know how we are using energy now and what would be the structure of a society that would survive without fossil fuels and without tyranny. In the first article in this series,[2] I argued that only electricity is a good long-term bet as an energy source, and explored how electricity is currently used. This article will look into the uses of petroleum and propose a simple model for a society that is logical, if somewhat fantastic. The initial task is to show what software engineers and others call “proof of concept”, “a short synopsis of certain ideas to demonstrate its feasibility [and that it] is probably capable of exploitation in a useful manner”, to paraphrase Wikipedia. The oil genieJust as critical to understanding electrical use in modeling a new system is the task of understanding how petroleum is used. Petroleum use in the United States is dominated by the private use of automobiles and light trucks, and as we shall see, is almost all used to power internal combustion engines in vehicles of some sort. In order to obtain a very fine-grained view of petroleum use, it is best to look at what are called the input-output tables of the US economy, maintained by the Department of Commerce: the most recent complete tables are from 1997 (the 2002 tables are overdue). Also, the data is in terms of dollars, not volume of liquids, but no other source gives us as much information.[3] I will look at the output of petroleum refineries to see how petroleum is used. It cost the oil companies about $57 billion to produce the petroleum refinery products — in other words, gasoline — used for private use in 1997 — in other words, basically cars and light trucks. This producer cost constituted only about 35% of the dollar output of all petroleum refineries. But when you add in the $52 billion for wholesale margins and the $32 billion for retail margins (plus the piddling $713 million for pipeline expenses), the resulting $144 billion that consumers wound up paying for gasoline in 1997 constitutes about 51% of the final price of all petroleum products. Air transport only pays about a 20% increase from producer to final purchase, and uses 4.3% of the country’s petroleum refinery output; but trucks pay more than half of the final cost between the refinery and gas tank, paying for 5.1% of the final petroleum product. Schools consume 2.5%, which I take to mean school buses, and all other forms of government transportation, 3.6%. Perhaps surprisingly, defense only takes .8%. If we add transportation used for retail and wholesale, transit, rail, the mail, and other miscellaneous uses, we add an extra 7%. So all transportation activities take up about 70% of the petroleum use in the United States.

The petroleum refinery sector itself uses up 5% of its own output, and pipelines use another 1.4%; asphalt and electricity generation, 1% each. For all kinds of petrochemicals, including plastics and pesticides, 3.2% of petroleum is used for feedstocks. What about lubricants so vital to the industrial process? .6%. For all construction activities, by which is meant construction equipment, 3.1% is used; for mining, 1%. All the tractors and combines and other critical agricultural machinery uses only 2.1%. While the machinery used for these activities looks impressive, and they use prodigious amounts per vehicle, just look at a picture of a freeway, and you will begin to understand that nothing on the planet uses energy the way the automobile fleet does. What about all the other kinds of manufacturing, from iron and steel to cars and trucks and planes, from semiconductors to clothes? A big fat 1.7%, thank you very much. Manufacturing uses electricity, some natural gas, and a little bit of coal. In fact, the services industry outside of those not mentioned above account for 3.8% of petroleum use, presumably for car and truck use for business purposes. Assuming that the petroleum used for manufacturing involves the factory and not business use of cars and trucks, then manufacturing, petrochemicals, lubricants, asphalt and electricity generation, account for 6.6% of petroleum use; over 90% of oil is used to power vehicle (assigning most of the petroleum refining oil use to vehicles). Take away the goo used for petrochemical feedstocks, and the conclusion is clear: without the internal combustion engine, there is no need for oil.[4] So then the question arises: how do we survive without the internal combustion engine? Without all of those “energy slaves” running around inside the engine, what do we do? Even if we tried to translate energy slaves into human slaves, what are we going to do, have 1,000 people pull a truck? And in any case, they wouldn’t be going very fast. Where have all the suburbs gone?Now it’s time for that proof of concept I promised; the concept being, what would happen if 80% of the population in the U.S. lived in a city the size of New York City? New York City has about 8.2 million people, as of 2006, and it is physically sited on about 300 square miles of land, or 786 square kilometers. The U.S. has about 300 million people, and 30 cities the population of the City of New York, as it is officially known, would mean that 240 million people would live inside a dense urban environment. The other sixty million, as I will explain, I assume will live in a ring around the cities, producing the food. The United State’s lower 48 states, that is, all the states besides Alaska and Hawaii, take up about 7,900,000 square kilometers. If 30 cities were as large as NYC, then they would take up only 3/10ths of one percent of the area of the lower 48 states![5] A big advantage to using New York City as a template is that NYC has the best mass transit system in the U.S. More than half of the residents do not own cars, and that figure rises to 75% in Manhattan. Let’s suppose that no one used a car in NYC. The subway system, which carries about half of the mass transit load, uses 1.8 billion kilowatt hours a year.[6] So let’s double that number to account for the 50% of the mass transit system currently constituted by diesel buses, double it again to expand it to the other approximately 50% of residents that own cars, and double it again to account for improved service. This is probably erring on the high side, since a carless NYC would probably use more light rail instead of more of the heavier subways. So a New York City with eight times the electricity usage for transportation would use 14.4 billion kilowatt hours per year for all private transportation. If all of our other 29 NYCs[7] were set up the same way, using 14.4 billion kilowatt hours per year for all of their private transportation needs, we would have a total expenditure of 432 billion kilowatt hours – about 11 percent of current US usage of approximately 4000 billion kilowatt hours per year. And we would eliminate most of the 50% of the petroleum used for the private consumption of oil! However, this still leaves longer distance travel for visiting other cities, much of which is now done by plane, and also freight rail service to replace trucks. And if you want to know what happened to all of the suburbs – they disappeared! Where have all the yeoman farmers gone?But what about food? We want a system in which

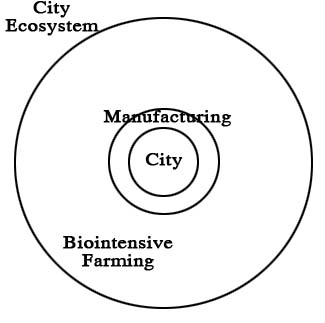

Fortunately, some farming movements have been developing that promise all of these. The best known may be permaculture, but I was able to obtain more usable numbers from a technology called biointensive agriculture, founded by John Jeavons in California. The question I wanted to know was, how much land would be needed to feed a population of 300 million well? According to Jeavons, the average American currently needs at least 15,000 square feet for food production. He claims that a vegetarian diet with vegetable sources of protein can be produced for one person using biointensive techniques on 4000 square feet.[8] Let’s assume, however, that we will add an extra 2,000 square feet to allow for some fish and raise some chickens, and that we will even make room for red meat lovers by letting the prairie reassert itself and culling a certain sustainable percentage from the millions of bison that again roam the plains. “And which NYC do you live in?”So we can envision each NYC-type city being surrounded by 8 million times 6000 square feet, or 48 billion square feet of farmland, or 1,722 square miles, in other words, about 6 times the area of the 300 square miles of the city. Let’s add another 1000 square feet per person for space for a manufacturing corridor around the city, and we can picture each prototypical city ecosystem in three concentric circles: the diameter of the circle is 3 times the diameter of the city in the center, that is, the city takes up 1/8th of the area of the entire city system; the manufacturing circle around the city takes up another 1/8th, and the farmland takes up a full 6/8ths. But since the area of all 30 cities only take up .3 percent of the area of the U.S., eight times that amount, will only take up 2.4%. There’s still plenty of room for the bison, and quite a bit else besides. In order to cultivate all of this farmland, I am assuming that for each 8 million person city, there will be 2 million people living in the farm areas who will do the biointensive gardening. Assuming about half of these will be working adults, we have one million people working full-time to feed all 10 million people in the city ecosystem. As Heinberg[9] has pointed out, probably at least 50 million people will be needed to grow crops if fossil fuels are not available. If we go down the road to serfdom, this would take place in a renewed plantation system. A permaculture/biointensive farming system would need no centralized institutional support, as our current industrial agricultural system does. In addition, it has been shown that small farms are more efficient than large farms,[10] although whether these methods would allow 1 person to provide the food needed for 10 needs to be further investigated. However, it may also be possible to grow a considerable amount of food within the cities as well. The social structure within the proposed city ecosystem could be just as important as the farming techniques and mass transportation. If the farms were set up as coops, and the manufacturing firms set up as employee-owned-and-operated firms along the lines of the Mondragon system[11] (along with the service firms within the city), then a new structure of power would begin to emerge from within the current system of domination. Just as capitalism grew from within the old slave/serf-based medieval systems, so a democratic/sustainable system could grow from within our hierarchical/fossil-fuel-based civilization. Still left to do: How do we supply electricity with solar/wind/geothermal energy? How do we provide high-speed and intercity rail, including an all-rail freight system, and how much electricity will that consume? How do we power construction, mining and other equipment, and replace natural gas, hopefully while reducing energy needs by making neighborhoods and buildings and factories more energy and materials efficient? Citizens of the world, read my next article, we have nothing to lose but our future chains. [1] For Rome, see Thomas Homer-Dixon, “The Upside of Down,”2006, chapter 2; for oil as an energy slave vs. humans as an energy slave, see Dale Allen Pfeiffer, Eating Fossil Fuels, 2006. [2] Singing the

nation electric, part

1. [3] The data for this analysis was obtained from the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis, from their Benchmark Input Output web page for 1997. I downloaded “1997 Standard Make and Use Tables at the detailed level”, which unzipped (unpacked) to yield, as one of the files, NAICUseDetail.txt. This has the raw data, but only shows codes instead of sectors such as “petroleum refinery”, meaning output of petroleum refinery. The descriptions that match the codes are in another of the files that was unzipped, IO-CodeDetail.xls. Using Microsoft Access, I imported both files and basically replaced the codes with the descriptions, copied those records having to do with energy, and particularly for this article, for the output of petroleum refineries. I will attempt to make all spreadsheets available when the next article is posted. [4] For a somewhat different methodology and distribution of oil uses, see Charles Komanoff, “Ending the Oil Age”, page 8. Komanoff shows 60% of oil volume going to cars, trucks, and planes, and 7.3% to freight, military, and recreation; and 10.3% to feedstocks. [5] These figures come from the Wikipedia entries for the United States and New York City. [6] 1.8 kilowatt hours comes from the journal IEEE Today’s Engineer, October 2004, “Straphanger Centennial Part III”, by May Ann Hoffman, available on-line . Figures for NYC mass transit use the following link. [7] If you want to follow this exercise further, you can look at the Statistical Abstract of the United States, in the Population section, table 25, “Large metropolitan statistical areas”, available as a spreadsheet. I hope to pursue this story line in a future article. [8] See “The man who would feed the world”, by Amy Stewart, April 13, 2002, San Francisco Chronicle, available online. Also see “Cultivating our garden”, from the journal In Context, Fall 1995, p. 34. [9] See “Fifty million farmers”. [10] See “Policy Brief No.4: The Multiple Functions and Benefits of Small Farm Agriculture,”September 1999, The Institute for Food and Development Policy”. [11] See my articles, “Why a democratic economy would be a more efficient economy”, and Why a democratic economy would be a more efficient economy, Part 2. | ||

|

| Register Free to receive updates of latest stories |

|---|

| Polls |

|---|

Meanwhile,

technology marches on, and the mundane transformation of ocean-going

cargo shipping along with the “sexy” high-tech of the internet has

paved the way for globalization. Like continents that collide and

allow some species to expand at the expense of others, the economic

elites of the richest countries have used their corporate

institutions to spread their power over the entire planet.

Agriculture has more and more become the province of a small set of

large corporations, even down to the genetic stock of the seeds; in

the U.S., more and more of the middle class has become weighed down

with indebtedness to global financial banks, and tied to a corporate

job so that they can try to receive adequate health care. Utilities

gobble up electricity-generating capacity, oil companies gobble up

each other. And for perhaps the first time in human history, one

society, the United States, expends the majority of the world’s

resources to create and maintain a war machine.

Meanwhile,

technology marches on, and the mundane transformation of ocean-going

cargo shipping along with the “sexy” high-tech of the internet has

paved the way for globalization. Like continents that collide and

allow some species to expand at the expense of others, the economic

elites of the richest countries have used their corporate

institutions to spread their power over the entire planet.

Agriculture has more and more become the province of a small set of

large corporations, even down to the genetic stock of the seeds; in

the U.S., more and more of the middle class has become weighed down

with indebtedness to global financial banks, and tied to a corporate

job so that they can try to receive adequate health care. Utilities

gobble up electricity-generating capacity, oil companies gobble up

each other. And for perhaps the first time in human history, one

society, the United States, expends the majority of the world’s

resources to create and maintain a war machine. But as

fossil fuels begin to run out, the global empires will suffer the

same fate as other empires that ran low on energy, such as Rome;

they will begin to collapse, as economies become more localized for

lack of fuel. Whether huge cargo ships can keep plying the seas

without fossil fuels is doubtful, so no matter what they do, a truly

global economy may be difficult to uphold; but more locally, if

history is any guide, the national/regional elites will do

everything in their power to hold on. And with much less energy to

work with, they will try to drive down the standards of living and

choices of the vast majority of the population and try to keep their

local empires going with a new kind of serfdom.

But as

fossil fuels begin to run out, the global empires will suffer the

same fate as other empires that ran low on energy, such as Rome;

they will begin to collapse, as economies become more localized for

lack of fuel. Whether huge cargo ships can keep plying the seas

without fossil fuels is doubtful, so no matter what they do, a truly

global economy may be difficult to uphold; but more locally, if

history is any guide, the national/regional elites will do

everything in their power to hold on. And with much less energy to

work with, they will try to drive down the standards of living and

choices of the vast majority of the population and try to keep their

local empires going with a new kind of serfdom. What about the rest --

construction, mining, agriculture, chemicals, electricity

generation? They are all relatively minor parts of oil consumption,

which brings up three points:

What about the rest --

construction, mining, agriculture, chemicals, electricity

generation? They are all relatively minor parts of oil consumption,

which brings up three points: